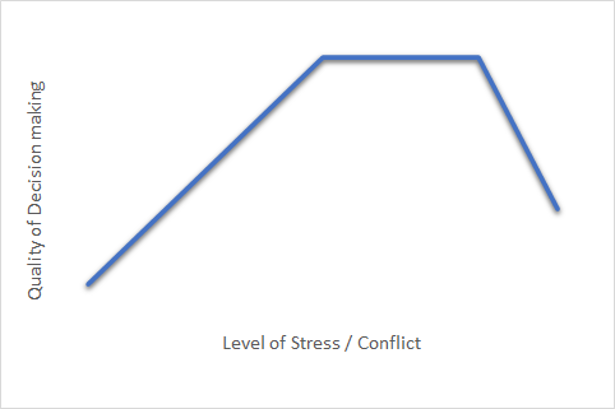

The Mediation Di-Stress Curve: Showing the Tension between Decision Making and the Stress to Get There

Have you noticed that different clients have different capacities for dealing with their conflict and stress? Have you also noticed that different professionals also have different capacities? While we professionals are in tune to, and often praise, the value of conflict, we can also agree that just because it has value does not make it easy. A crucial skill for our professional field is to know when we are reaching a person’s limit (whether our client’s, or our own), because if we ignore that threshold, the mediation or collaborative negotiation will likely come to a crashing halt.

Have you noticed that different clients have different capacities for dealing with their conflict and stress? Have you also noticed that different professionals also have different capacities? While we professionals are in tune to, and often praise, the value of conflict, we can also agree that just because it has value does not make it easy. A crucial skill for our professional field is to know when we are reaching a person’s limit (whether our client’s, or our own), because if we ignore that threshold, the mediation or collaborative negotiation will likely come to a crashing halt.

In this article, I would like to share a useful tool that demonstrates the relationship between a person’s capacity for stress and how that capacity impacts the quality of decision making. But first, let’s look how this plays out daily in our work:

- Wife is not interested in working on her budget “to count up how much she spends on manicures and pedicures”, she just wants to figure out how much spousal support she will get.

- At every session, your client keeps on asking if they can just finalize the deal now and have it written up even though they have barely worked through the terms.

- Financially savvy hedge fund owner cancels first 5-way meeting for being up all night, unable to sleep due to his stress about meeting face to face with his wife.

- Financial neutral is anxious about not having a resolution yet and says that we either need to make a deal at our next meeting or tell the clients that this process will not work for them.

- Husband is running out of patience with your process and asks if we can just come up with a solution.

In our professional ivory towers we know that by honoring the conflict, staying with the process, developing a deeper understanding as to what is important for both sides, we will usually come to a resolution that optimizes parties’ needs and interests. But that takes time and safety. Not all of our clients (or ourselves) are able to stay the course.

Let’s take a look at this graph which depicts the relationship between these two tensions.

Initially, for most people in conflict or having some minimal level of stress, through staying the course, working through different perspectives, although stressful, the quality of decision making grows. Some level of stress is actually a good thing, it is called “eu-stress”, as some level of stress is useful. We are not just making a decision from our own perspective but can factor in the perspective of the other. As long as the stress can be handled, there is productive value in working through those differences.

But as the level of stress increases, at some point that stress becomes distress and ends up being unproductive, if not destructive. As stress increases, at some point the benefit plateaus and, if it continues, the quality of decision making will come crashing down the cliff, as portrayed in the graph. Too much stress leads to fight or flight, defensiveness, or withdrawal. No longer is the goal to get to the best solution. They just need to end the stress.

Our challenge as conflict resolution professionals is to allow for enough stress to receive the gains of optimal solutions without the losses of the distress.

Tips for practice:

- Consider how, as professionals, we can increase the tolerance of our clients being in a place of stress, of being in that stressful place of unknowing. All too often settlements are reached based on the person with the lowest capacity to handle conflict. How can we support that client to better handle the stress to help him or her reach better outcomes?

Some practical suggestions might include:

-

- Trying to understand where the stress is coming from and work together to alleviate it directly. For example, tensions in the home while living under the same roof can get to the best of us. Can this stress be addressed? Can the status quo be improved or stabilized to provide a more stable environment to work things out with a clearer mind?

- Can other professionals help, whether attorneys or mental health professionals who can directly support the client negatively impacted by the stress?

- Could caucusing be appropriate? And, is there room to be more open to caucusing where we are only doing zoom mediations and don’t have the opportunity to connect face to face with a client?

- One tool that I use to address the approaching distress of clients is by making the tension noted in this article (between quality of decision making and stress) explicit. I actually show them the above graph and ask them where they think they are at with their stress levels. Can they see the value of staying the course in order to make better decisions? By being transparent with our client, making the implicit explicit, identifying this tension, its risks and benefits, we are helping our clients make more informed decisions and assessing how we can best help them.

- Lastly, let’s not forget about our own capacity for stress and its impact on how we handle a particular case or client.

I hope that you found value in this article and in taking a look at this graph. I would love you to share any further thoughts and feedback on these ideas.

Latest Blogs

To read our next article discussing the New York v. New Jersey: Separate Property Contributions to Real Estate? click here.

To read an article on Meeting Faces on Screens vs. Masks In-Person? click here.